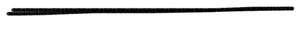

Universities across the U.S. collectively conjured the illusion of thousands more female athletic opportunities by abusing federal reporting rules.

Fifty years after the passage of Title IX, the landmark law banning sex discrimination in education, colleges and universities are circumventing its intent by manipulating athletic rosters to appear more balanced than they are.

By packing their women’s teams with extra players who never compete, double- and triple-counting women while undercounting men and even classifying male practice players as women, schools across the nation collectively conjured the illusion of thousands more female athletic opportunities, a USA TODAY investigation found.

At Florida State University, for example, more than half of the 66 women on its indoor track and field team never competed indoors. The school simply counted all its outdoor track athletes twice.

The University of Wisconsin claimed to have 165 athletes on its women’s rowing roster even though more than a third of them never raced for the school. Some of the women quit before the regular season even started.

At the University of Michigan, 29 athletes on the 43-player women’s basketball roster were actually men who signed up to practice with the team.

It is a far cry from what former U.S. Sen. Carol Moseley Braun of Illinois envisioned when she co-sponsored a complementary law in 1994 requiring schools to report their athletic numbers to the federal government.

“I think they’re sleazy,” Braun told USA TODAY. “Come on – this is people trying to avoid complying with the law. People know they shouldn’t do it, and they do it anyway.”

Title IX was supposed to close the gender gap in college athletics by requiring schools to provide men and women equitable opportunities to play sports.

Instead, the reporting found, schools have abused accepted rules in ways that allow them to comply with the letter of the law while violating its spirit.

In a comprehensive data analysis, USA TODAY found widespread use of roster manipulation across many of the nation’s largest and best-known colleges and universities.

While some of these techniques are well-documented and individual schools have been exposed for using them, USA TODAY’s reporting reveals the problem is pervasive throughout the highest echelon of college sports.

USA TODAY compared the athletic participation numbers schools report to the U.S. Department of Education against four different data sources: NCAA reports, online rosters, internal rosters called "squad lists" and reams of competition results. Reporters interviewed 51 Title IX experts and attorneys, lawmakers, athletes, coaches and athletic department administrators.

The news organization’s analysis centered on 107 public schools in the Football Bowl Subdivision – the highest level in Division I – during the 2018-19 school year, the last full year before the pandemic upended the college sports landscape. USA TODAY filed hundreds of public records requests for the schools' squad lists and gender equity reports to the NCAA and wrote computer programs to collect online rosters and stats.

The vast majority of those schools counted athletes in a way that inflated the reported number of female participants. Sixty-six did so by at least 20 athletes, USA TODAY’s investigation found. Altogether, the schools added more than 3,600 additional participation “opportunities” for female athletes without adding a single new women’s team.

Among the investigation’s findings:

• Schools in the analysis created 2,252 women’s roster spots by double- and triple-counting existing athletes – a controversial counting method the Department of Education permits. They double-counted women nearly 50% more often than men and triple-counted women 70% more. The University of Hawaii netted 78 women’s roster spots through duplicate counting alone – more than its men’s baseball, basketball, tennis and volleyball teams combined.

• Twenty-seven schools stuffed their women’s rowing rosters with more athletes than needed, including some that added dozens of novice rowers with no experience who never competed in varsity races. Their teams averaged 87 women – more than double the maximum number most conference championships allow. Based on roster caps set in federal lawsuits at two Division I rowing programs, at least 838 female rowers – more than one-third of all female rowers counted – filled unnecessary roster spots.

• At least 1 of every 4 women’s basketball players the schools reported to the federal government were actually men. Fifty-two schools counted as female participants at least 601 men who scrimmage with women’s basketball teams. Advocates have repeatedly urged the Department of Education since 2013 to stop letting schools count male practice players toward women’s teams, but the agency has not addressed the problem.

At the same time, 10 schools undercounted a total of 170 male athletes by claiming to sponsor no men’s indoor track and field team while continuing to send men to indoor track and field competitions. These athletes did not compete in conference or NCAA indoor championships, so their schools did not count them. Miami University of Ohio, for instance, sent 48 male athletes to participate in indoor meets in 2018-19, meet records show, but counted zero in gender equity reports.

The U.S. Department of Education, which oversees Title IX compliance, has done little to rein in number padding. Courts have ruled that athletes must receive “genuine” participation opportunities in order to count. But the department allows schools to report inflated numbers without assessing whether the opportunities are legitimate.

The department publishes the schools’ reported numbers online as required under the 1994 Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act, or EADA. The law’s purpose was to give the public the tools to search a school and assess if it offers men and women equitable opportunities.

Yet the schools say those numbers shouldn’t be used to assess their Title IX compliance. Instead, they keep the real numbers in-house, making it tougher for the public to notice inequities and take action by complaining to the department or filing a lawsuit.

The Department of Education should be vigilant in enforcing compliance, Braun said. But often, the only times schools are held accountable is when the discriminated party – female athletes – files a federal complaint or a lawsuit.

"I distinguish between what I’ll call falsifying the numbers and taking advantage of the rules," said Arthur Bryant, an attorney who has litigated Title IX cases for decades. "I don’t think you can really accuse the school of doing anything wrong if it is playing by the rules. Then it’s the rules that need to be fixed.”

USA TODAY reached out to 15 schools for comment about their use of counting techniques that boosted their female-athlete totals. Athletic department officials said they followed federal guidelines and denied any intention to deceive.

The Department of Education declined a request by USA TODAY to make officials available for an interview. Instead, it emailed a statement saying that EADA and Title IX are two different laws and that "it is not possible to draw legal conclusions about an institution’s compliance with Title IX from EADA data."

The agency additionally provided a statement by Catherine Lhamon, its assistant secretary for its Office for Civil Rights (OCR).

“Every school, whether investigated by OCR or not, has a Title IX Federal obligation to ensure equal opportunity among men’s and women’s athletics," Lhamon said. "While we have come a long way in the 50 years since the passage of Title IX in terms of creating more opportunities for women in higher education athletics, all school communities need to complete the task to fulfill the law’s promise."

Lhamon said in her statement that the data reported by schools to the federal government "tell part of the story in evaluating whether a school offers equitable athletic opportunities" but that the agency looks closely at other factors when determining compliance with the law.

Yet requiring schools to report numbers was supposed to be “the first step to increase compliance with Title IX,” then-U.S. Rep. Cardiss Collins said in a 1993 subcommittee hearing on intercollegiate sports during which she introduced the bill that became the EADA. Collins, who died in 2013, spoke then of the need for stronger enforcement from the department and how colleges and the NCAA would not “do the right thing” unless forced.

Nearly 30 years later, little has changed, said U.S. Rep. Lori Trahan, D-Mass., who played volleyball at Georgetown University in the 1990s.

"This is just the latest example of the NCAA and its members long undervaluing and mistreating women athletes," Trahan told USA TODAY. “Lying about women athletes is just the cost of doing business."

Which schools inflate their women’s rosters

Double- and triple-counting athletes

When Title IX passed in 1972, college men outnumbered women in both the classrooms and the locker rooms. Five decades later, women outnumber men in the classroom but not on the courts or fields.

As female college enrollment rates climbed from 43% the year of the bill’s passage to nearly 60% today, colleges and universities have failed to maintain proportionate ratios in athletics. As of 2019, women represented just 44% of NCAA athletes nationwide.

Proportionality is one of three ways schools can show compliance with Title IX. It requires the gender breakdowns of colleges’ varsity athletic programs to reflect their student bodies.

The other two are showing a history and continuing practice of increasing the athletic opportunities for the underrepresented sex – usually women – or demonstrating that the athletic interests and abilities of their female students are met.

Among the three, proportionality is considered the safest route.

For many schools, balancing triple-digit football rosters with gender equity requirements means adding new women’s sports, each of which could carry a hefty price tag.

Clemson, for example, will spend $12.5 million on new facilities and an estimated $1.7 million annually to field a women’s lacrosse team as part of an agreement to boost its female athletic participation rates, school spokesman Jeff Kallin told USA TODAY.

Instead of paying those bills, it’s easier for schools to manipulate their existing rosters.

Double- and triple-counting is one of the most widely used and efficient ways to boost a school’s number of female athletes without adding new recruits or new teams.

And it is allowed. The federal government says schools can count athletes more than once if they compete on more than one team. Rather than counting heads, schools tally the number of “participation opportunities” – in other words, roster spots – they fill each year.

Some athletes do compete in multiple sports – the EADA reporting guide gives an example of someone who plays football and lacrosse – but nowhere more so than in cross country, indoor track and field, and outdoor track and field. The department and NCAA instruct schools to count those as three separate teams despite significant roster overlap.

Track and field and cross country athletes are the only athletes who regularly compete on more than one team. They accounted for 98.1% of all duplicated roster spots in 2018-19, according to USA TODAY’s analysis of the 95 FBS schools that indicated double- or triple-counting on their gender equity reports to the NCAA. Unlike the EADA reports, NCAA reports break down duplicated counts by sport.

That makes these athletes inherently worth more than their peers for Title IX counting purposes. And schools take advantage.

While men’s track and field and cross country rosters are generally lean, schools often stuff women’s teams full of athletes they do not need, even though they compete in the same types and number of events. Some women's rosters ballooned to two or three times the sizes of their men’s teams.

Take Florida State. Although only the top five runners for each team score points in cross country meets, Florida State packed its women’s cross country team with 43 people, while the men’s team had 13. It triple-counted 38 of the women, even though less than a third competed during all three seasons, USA TODAY’s analysis of 2018-19 squad lists and meet results found.

In track and field that year, Florida State counted only 38 of its 45 male athletes toward its indoor and outdoor squads, but it did so for all 66 of its female athletes. More than half of those women, the analysis found, did not compete in any indoor meets that year.

One of them was Kelly Aponte, who said she was surprised to learn she had been triple-counted. She competed during the outdoor season that year, but injuries prevented her from running in any indoor or cross country meets.

“I was still going to practice and training, but I never actually raced,” said Aponte, a 2020 graduate.

“I was not a top 10 runner. I had zero business being in an (Atlantic Coast Conference) competition,” she said. “It would have been a stupid move on the coaches’ part to put me in an ACC race.”

By double- and triple-counting athletes like Aponte, the school claimed to have offered 175 track and field and cross country "opportunities" to women. That erased half of its overall gender participation gap that year.

Florida State athletic director Michael Alford said his school “consistently supports” women’s programs at a championship level and last added a team – beach volleyball – in 2011.

“We report our participation data in accordance with the policies and guidelines provided by the U.S. Department of Education and established industry practices.”

Balancing out “a 120-man football roster” with "a 45-person women's track and field team" whose athletes are counted more than once is not the same as providing equitable opportunities, said Russell Dinkins, a former Ivy League track champion and executive director of the Tracksmith Foundation, a nonprofit that aims to increase track and field participation and helps college teams avoid program cuts.

That Title IX compliance hinges on roster spots and not distinct athletes, he said, must be reexamined.

"I think it does a disservice to women," Dinkins said.

Even with the roster manipulation, USA TODAY’s analysis found, Florida State would have still needed to add more than 100 female athletes to reach proportionality – roughly the equivalent of its entire football team.

Elevating women’s lacrosse would have gotten it part of the way there.

Multiple times, including as recently as last fall, members of the school’s 28-member women’s lacrosse club have asked the school to be an officially sanctioned NCAA sport, said 2021-22 club officers Sophia Villalonga and Erica Simkins.

There’s growing interest in the sport and a recruiting hotbed in the state, they said. Nine of the other 14 ACC schools sponsor women’s lacrosse.

But the school rejected their request.

Villalonga and Simkins said they didn’t know Florida State’s proportionality was so out of whack or that it manipulated its roster count. Had they, the lacrosse players might have pushed harder at their last meeting with school administrators.

“The girls on our team, they’re not aware of this at all,” Simkins said. “I coach a high school team and, man, we’re never going to be the ones to benefit from this, but all these high school girls would. It’s a growing sport – so many of these girls want to play in college.”

The problem across many schools often comes down to who’s doing the counting and reporting, said Marianne Vydra, a retired Oregon State University athletics administrator. For example, during her tenure, Vydra was supposed to review the numbers before the athletic department’s business office submitted them, she said, but once, it didn’t show them to her until afterward.

She couldn’t believe what she saw.

“At one point we had female hammer throwers counted as indoor track athletes. What?” she said. “Nobody is throwing a hammer indoors.”

Padding the rowing rosters

Every fall, the University of Wisconsin women's rowing team hosts an "open house" at its three-story boathouse on the edge of campus bordering Lake Mendota.

Any woman on campus can come learn about the team and, if interested, join.

"If you were a competitive athlete in high school and ever dreamed of becoming a D-I college athlete, this is your opportunity to represent the Wisconsin Badgers," read a post on the athletic department website ahead of last year's event.

Dozens of walk-ons, many of them freshmen, started working out with the team alongside returners and women recruited out of high school. Many quit before the competitive season in spring. Others stayed as novice rowers who may get to race in a novice boat and serve as varsity reserves but do not get their photos and bios on the athletic department website.

A total of 57 women raced in Wisconsin's varsity openweight and lightweight boats during the 2018-19 season. But when the school reported its gender equity numbers to the federal government and the NCAA, it claimed 165 female rowers – more than its football, men's basketball and men's hockey teams combined.

Multiple former rowers contacted by USA TODAY described an experience that frustrated them and was not close to what had been advertised. As D-I athletes they expected cool gear, exciting road trips and high-level competition – instead, most of them didn’t leave the boathouse.

Teyha Crego said she spent her freshman semester with the team relegated to the "land crew." She trained in the boathouse on rowing machines and in "the tank," a rowing simulator. She went on runs up Bascom Hill. She never got on the lake.

Isabelle Smiley joined the team after being approached about open tryouts at freshman orientation. She left after six months because of injury concerns, but she was shocked when she heard how many rowers Wisconsin claimed to have. She noted only about 40 rowing machines fit in the boathouse.

“I cannot fathom there ever being 170 girls,” said Smiley, who graduated this spring. “That’s a crazy number.”

A USA TODAY analysis of Wisconsin’s squad list and regatta records found that at least 64 of those women did not compete in any races that year. Another 44 competed only in scrimmages or novice boats.

Justin Doherty, a Wisconsin athletics spokesperson, said athletes on many of its teams do not compete outside of practice, but that “doesn’t necessarily mean their experience as a student athlete is diminished in some way.”

“Some remain in the program and others decide it is not for them,” Doherty said. “We don’t consider their experience to be of second-class caliber.”

Colleges have long leaned on women's rowing teams to offset football teams. The capacity for large rosters, said former University of Massachusetts women’s rowing coach Jim Dietz, has been a major selling point for the sport since 1997, when the NCAA sponsored the first women’s rowing championship.

"It was cheaper to hire a couple of coaches to coach somewhere (from) 65 to 80 women than it was to hire three coaches of three different sports to coach 20 women apiece," said Dietz, who retired from UMass in 2019 after 25 years as head coach. "Here, you're getting a sport that is normally off campus on a river that does not cost you anything to be there. It was very attractive for these guys. It was the easy thing to do."

Rather than adopt an Olympic model for the sport that would have involved more races and boats, the NCAA adopted a scaled-down, team-based model whose championship accommodates a maximum of 23 women per school.

Conference championships sometimes provide for additional boats. The Big Ten championship, for instance, accommodates up to 51 women – more than any other conference. Most others permit fewer than 30.

But those limits have not stopped schools from jamming as many women onto their rowing rosters as possible.

In addition to Wisconsin, the University of Alabama, the University of Tennessee and Michigan each reported triple-digit women’s rowing teams. Alabama reported 122 rowers despite its conference championships allowing for 28.

Of the 30 schools in USA TODAY’s analysis that sponsored women’s rowing, only four – Wisconsin, the University of Washington, Oregon State University and the University of California, Berkeley – sponsored men's rowing. Their average roster size was 60, based on their reported numbers to the federal government.

The roster stuffing happens despite the fact that, when challenged in court, women’s rowing teams have been capped at much lower numbers.

The University of Iowa agreed in October to reduce the size of its 94-member squad to no more than 75 athletes. The concession came after members of Iowa’s women’s swim team, which the school tried to cut in 2020, sued the school, saying in part that its rowing count was inflated to skew its overall number of female athletes and that it didn’t comply with Title IX.

The University of Connecticut settled a lawsuit in December that capped its women's rowing team at 45 after a group of female rowers alleged similar roster inflation when the school tried to cut the team. Jennifer Sanford, the head coach, testified that athletic department officials directed her to keep at least 60 women on her roster, even though she said she needed no more than 42.

Iowa and Connecticut’s caps allow for the maximum number of rowers at their conference championships, plus nearly half that number of women to act as reserves. Based on those caps, 27 of the 30 FBS schools with women’s rowing teams in 2018-19 rostered more women than needed, the analysis found.

Roster stuffing, Sanford told USA TODAY, “is happening at most Division I schools that have football.”

“They are just not getting looked into,” she said, “unless there is a lawsuit.”

Counting men as women’s participants

Cruz Vasquez spent his junior and senior years at the University of Oregon as a practice player for the women's basketball team. He regularly drew the toughest assignment: guarding two-time national player of the year Sabrina Ionescu.

"I was fighting for my life every day," Vazquez said. "Talk about humbling."

Schools commonly invite male students to scrimmage with women's teams as a way of preparing them for bigger-bodied opponents while keeping their own players rested. Most common in basketball, practice players also appear in women's volleyball, soccer, lacrosse and other sports.

Though Vazquez benefited from some advantages afforded to all athletes – including 24/7 access to Matthew Knight Arena, the Ducks’ home court, and the athletes-only tutoring center – he was surprised and annoyed to learn Oregon counted him in a 2018-19 gender equity report as not only a full participant on the basketball team but also as a female athlete.

Oregon counted a dozen such men as women in its EADA report to the Department of Education that year, USA TODAY found, including 11 in women's basketball and one on the beach volleyball team.

"That’s ridiculous," Vasquez said. "That definitely bothers me. Female athletes have worked too hard for too long to be this disrespected. It’s 2022 – how are women not being given all the same opportunities yet?"

The Department of Education instructs schools to count male practice players as women’s team participants in their annual Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act reports.

Half the schools in USA TODAY’s analysis did not report male practice players on their women’s basketball teams. Those that did counted almost as many men on their women’s basketball teams as women.

“We follow the guidelines as issued on the EADA reporting form,” Oregon athletic department spokesman Jimmy Stanton told USA TODAY.

The database where the department publishes schools’ data shows how many of the participants counted were male practice players – but only for the current year. The online database does not display that information for previous years.

When USA TODAY asked the department why it instructs schools to report numbers this way, a spokesperson pointed back to the EADA reporting guide and regulations, which do not provide an explanation.

The result is a misleading picture that makes schools look better than they are at providing equitable playing opportunities to women.

USA TODAY compared EADA numbers with those schools reported to the NCAA, which instructs them not to count male practice players toward women’s teams. It flagged differences of three or more athletes.

It then reviewed each team’s squad list to check for players whose names did not appear on athletic department websites. Dozens of women’s squads were filled with Jasons, Roberts, Michaels and Brandons.

Overall, the counting method disproportionately inflated female athlete counts, USA TODAY found – 90% of athletes flagged as possible practice players were on women's teams.

Michigan had the highest count of any school in the analysis, reporting 36 practice players across three women's sports. The 29 on its women's basketball team was more than double its number of actual female basketball players.

In an interview with USA TODAY, Michigan women's basketball coach Kim Barnes Arico said the high number ensured her team would never be short practice players because of scheduling conflicts. When Barnes Arico was asked if she knew the athletic department counted the men toward its women’s teams, a school spokesperson, Sarah VanMetre, interrupted and ended the interview.

Arizona State counted 34 practice players across its women’s teams, including 24 in basketball, eight in volleyball and two in water polo.

Neither Arizona State nor Michigan reported any practice players on men’s teams.

Paige Shacklett, the Arizona State athletic department’s corporate public relations specialist, told USA TODAY the school reports the numbers the way the Department of Education instructs. It counts male practice players only for EADA reporting, she said – it would not count them as women if the federal government were to launch a Title IX compliance review.

“Universities that accurately report the use of male practice players in connection with their women’s sports do not obtain an advantage in terms of their Title IX compliance obligations, as your questions suggest,” Shacklett said.

Shacklett said Arizona State officials “do not believe there is tension between the EADA and Title IX compliance as they are two separate requirements.”

The Department of Education should stop letting schools count male practice players as roster spots for women, said Neena Chaudhry, general counsel for the nonprofit National Women’s Law Center. Of all the problematic counting methods, it is the easiest to fix.

“The point of this law is to provide the data to students who might be thinking about what schools they want to go to, to parents, to advocates,” Chaudhry said. “It is basically the best data the public can look at, and so it’s absolutely essential that the data is accurate.”

Chaudhry and the National Women’s Law Center complained to the Department of Education about the issue in 2016 during a required review of EADA reporting procedures. Counting male practice players as women’s team participants, their letter said, can “distort the analysis of whether participation opportunities are being allocated equitably on the basis of sex.”

The Women’s Basketball Coaches Association raised the same concerns in 2013, urging the department to revise EADA reporting instructions so that no athletes of one gender are listed in counts of the other.

The department does not appear to have acted in response to either complaint. It announced a new 60-day public comment period for the law on May 6.

Trahan, the Massachusetts congresswoman and former Georgetown University volleyball player, called schools’ use of roster padding techniques “indefensible.”

“Shame on the complicit athletic directors and college presidents turning a blind eye to this injustice, and the NCAA should be embarrassed for their role in it as well,” Trahan said. “What’s even worse is that if you asked almost every woman who’s played or is playing college sports, they would tell you they’re not surprised.”

Contributing: Indiana University's Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism and Knight-Newhouse Data project at Syracuse University